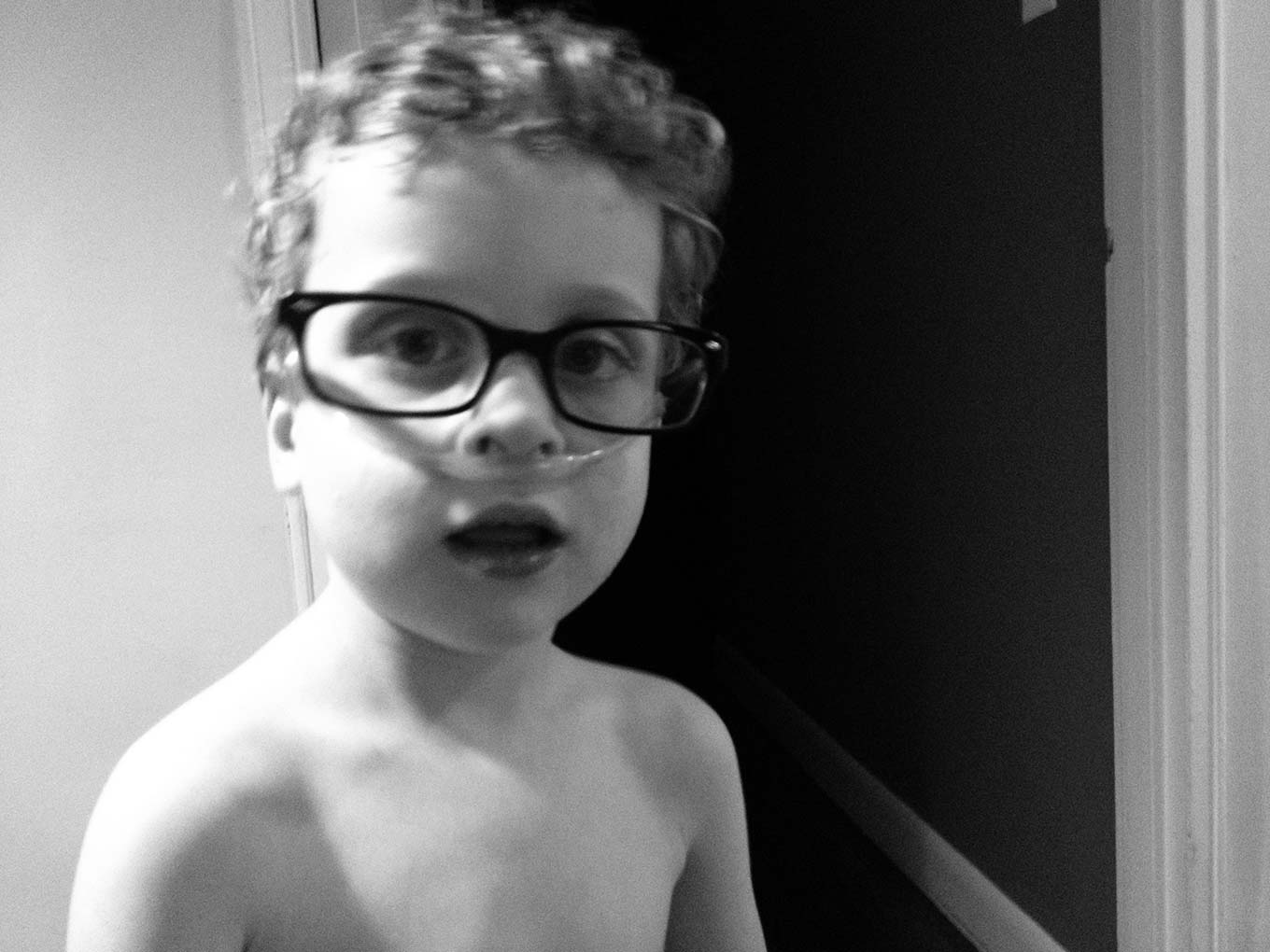

It's hard to believe we lived over 2.5 years with 24/7 oxygen equipment — tanks, compressors, tubes — attached to our son no matter where we went. We kept explosive O2 tanks in our home, traveled with them in our car. We wrestled with yards of cumbersome (and tangle-some) tubing wherever we went. It wasn't easy and I didn't always handle it well, though C always did.

It's hard to believe we lived over 2.5 years with 24/7 oxygen equipment — tanks, compressors, tubes — attached to our son no matter where we went. We kept explosive O2 tanks in our home, traveled with them in our car. We wrestled with yards of cumbersome (and tangle-some) tubing wherever we went. It wasn't easy and I didn't always handle it well, though C always did.

We'd constantly do oxygen math: "Okay, if we're going out for 2 hours, and he's at 1 liter per minute, we should be good with one or two tanks." "We have 7 full tanks in the closet, so if we only use two tanks a day we won't need another delivery for about three days."

We endured the stares of strangers who probably wondered why we were traveling with a tiny spaceman. We had prolonged hospital stays where we felt totally isolated and alone; scary periods where no one could tell us what was going on or if C would even survive; and watched as C was put under anesthesia a few times, including once for a lung biopsy.

But that's all over now. Last week was the one-year anniversary of our pulmonologist giving us the green light to take C off oxygen.

We still use a pulse oximeter at home and school to make sure C's "sats" — oxygen saturation levels — are good (they are). We still need to be careful about viruses and other airborne nasties. And we'll likely never know whether the disease is actually gone or simply in remission. Plus, there are still a couple more tests the specialists want to do — a sleep test and something called a hypoxic challenge test to see if C can travel on an airplane (C has never met his grandmother who lives in California because her health problems prevent her flying, and we still don't have the green light to put him on an airplane).

Still, things could have been so much worse, and for many of the parents we met through the chILD Foundation, they are.

So once again, as rough as things have been, we're grateful and appreciative for how they're turning out.

Stay healthy, C. Your parents are a little exhausted.

Shortly after C's diagnosis I began reading everything I could on autism. I focused on possible causes, potential therapies, and what we might do to make things better.

Shortly after C's diagnosis I began reading everything I could on autism. I focused on possible causes, potential therapies, and what we might do to make things better. C is a boy who, at four, can read full sentences, complex words, and short books; if it's 6:51, he can tell you how many minutes until it's 6:58; he's memorized nearly every street in our neighborhood and can represent them with toy train tracks; he knows all the stops on the Q train from here to Brighton Beach; he knows the color of every single NYC subway line; if you ask him what number J is, he'll say "ten" without hesitation, because that's where J falls in the sequence of letters in the alphabet.

C is a boy who, at four, can read full sentences, complex words, and short books; if it's 6:51, he can tell you how many minutes until it's 6:58; he's memorized nearly every street in our neighborhood and can represent them with toy train tracks; he knows all the stops on the Q train from here to Brighton Beach; he knows the color of every single NYC subway line; if you ask him what number J is, he'll say "ten" without hesitation, because that's where J falls in the sequence of letters in the alphabet.