What do you envision when someone says, "autism spectrum"?

Like most people, you probably imagine a line going from mild to severe, or good to bad, or something similar. At one end would be neurotypical (non-ASD), at the other severely autistic.

The problem is that's not how the spectrum works. I learned this when C was diagnosed and I, like any parent, wanted to find out where he was on this so-called spectrum. Was he in the middle? Toward the more severe end?

It wasn't that the experts couldn't or wouldn't answer me. It's that I was asking the wrong question. I wanted to be able to plot his autism on a linear scale, but the autism spectrum isn't linear at all.

So I did my own research to figure out what C's autism looked like. I felt like visualizing it would help me understand where his strengths and weaknesses were. However, several trips to Google left me more befuddled than ever: there wasn't any agreed-upon visualization of the autism spectrum.

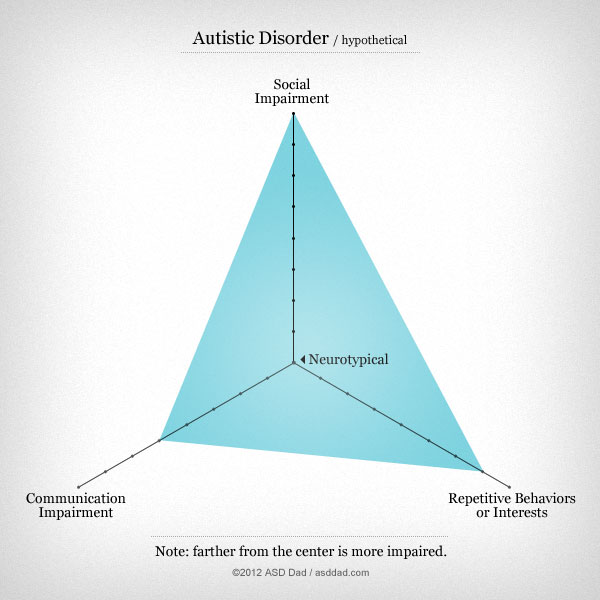

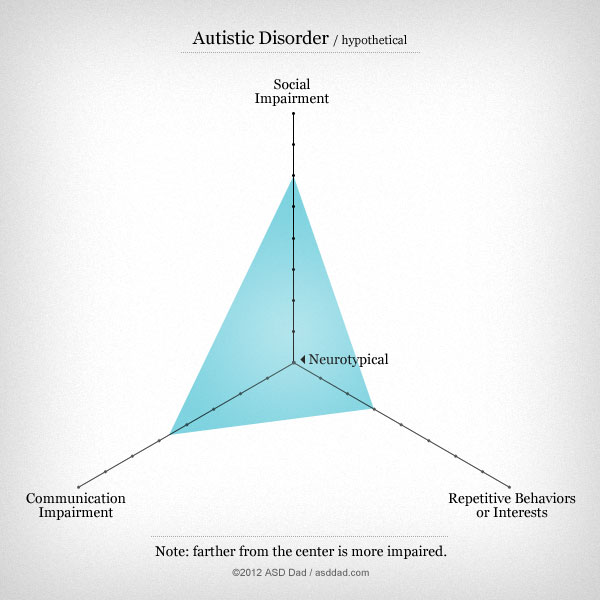

Since I earn my living trying to make complex things simple and easy to understand, I decided to create my own autism spectrum diagram, something that would provide a more accurate representation of the condition.

I based my visualization on the fact that there are three generally accepted axes for ASD: social, communication, and behavioral.

On each axis, the range goes from typical — what we'd expect to see in a non-ASD individual — to severely impaired. Here are the generally accepted criteria for each axis:

Social Impairment

Problematic nonverbal behaviors; failure to interact appropriately with peers or make friends; playing alone while other children the same age approach each other, cooperate and imitate each other; problems sharing interests, achievements or pleasure with others; problems responding to social and emotional cues.

Communication Impairment

Delay or absence of speech with no attempt to compensate by using gestures; an inability to carry on a conversation even when speech is adequate; stereotyped and repetitive language; lack of imaginative play.

Repetitive Behaviors or Interests

An interest of intense or abnormal focus; rigid adherence to a routine or ritual that has no purpose; repetition of particular movements or gestures; persistent preoccupation with parts of objects.

My Visualization of the Spectrum

My diagram helps visually distinguish the three primary forms of ASD — Autistic Disorder, Asperger Synrdome, and PDD-NOS — from one another. (C has Autistic Disorder.)

Plotting the level of impairment is subjective, of course, and one's point on each axis may change over time, with therapy and other treatments. Nonetheless, what my diagram shows is that the so-called autism spectrum doesn't result in a single point plotted on a line, but several points that create a shape, a map of each individual's unique ASD landscape.

Of course, the diagrams above are hypothetical, not based on any particular individual. In reality, each individual would map differently based on their own levels of impairment.

What Do You Think?

My diagram is a work in progress. I'm not formally educated in ASD, obviously, but I felt this format was helpful. What do you think? Let me know.

C's biggest obsession is letters and numbers: he sees them everywhere, and even though he just turned 3, he's already starting to spell words. (Some people have suggested he might have

C's biggest obsession is letters and numbers: he sees them everywhere, and even though he just turned 3, he's already starting to spell words. (Some people have suggested he might have

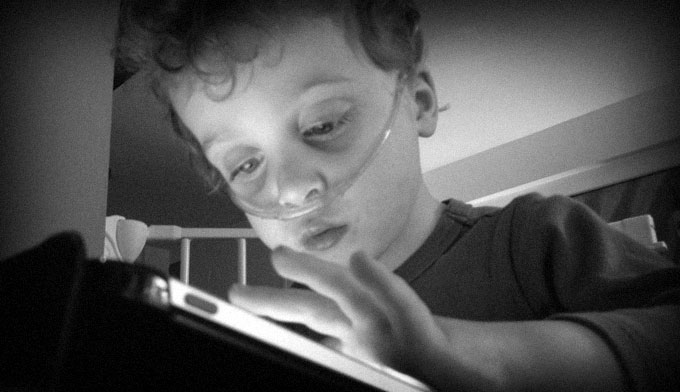

Sunday isn't a day of rest for C: he had four hours of ABA therapy, including a two-hour session with a brand new therapist; later, we went to the park and the big playground, where he ran around disconnected from his oxygen for over an hour. Later, we watched ducks and geese in the big pond, before coming home for dinner, baths, and bed.

Sunday isn't a day of rest for C: he had four hours of ABA therapy, including a two-hour session with a brand new therapist; later, we went to the park and the big playground, where he ran around disconnected from his oxygen for over an hour. Later, we watched ducks and geese in the big pond, before coming home for dinner, baths, and bed.

I'm so glad to be playing racquetball again, if only one or two times a week. I walk through the glass doors, into the large empty court, and for sixty minutes I'll think only about the game: serve, return, volley, kill shot — the action so fast there isn't time to think of all the things that are constantly eating away at me.

I'm so glad to be playing racquetball again, if only one or two times a week. I walk through the glass doors, into the large empty court, and for sixty minutes I'll think only about the game: serve, return, volley, kill shot — the action so fast there isn't time to think of all the things that are constantly eating away at me.